On August 12, James Alex Fields Jr., described by his high school history teacher as “deeply into Adolf Hitler and white supremacy,” drove a car into a group of counterprotesters, murdering 32-year-old Heather Heyer and injuring 19 other people. Earlier in the event, Fields was seen marching with a Vanguard America shield. That same day, a group of six white men followed 20-year-old Black special ed assistant teacher DeAndre Harris into a parking garage and beat him with poles and metal pipes, an attack that was caught on film and posted to the internet. In response to the racist violence, Trump famously said that there were “very fine people on both sides.”

The Unite the Right rally, like much of the American fascist movement’s activism during the 2017–2021 Trump presidency, was largely organized online using Discord, a group chat platform designed for gamers. In Discord, users join servers, a group of chatrooms, or a channel, a single chatroom. Each channel covers different topics. Fascists created Discord servers for their regional hate groups, as well as for projects like organizing Unite the Right.

An antifascist infiltrator gained access to the server used to organize Unite the Right, called Charlottesville 2.0, as well as many other servers used by fascists at the time. They then leaked the chat logs to Chris Schiano and Dan Feidt, journalists working with the independent nonprofit news collective Unicorn Riot. The leak took the form of screenshots from the Discord app, large JSON files containing thousands of messages, and audio recordings from voice meetings.

In this chapter, I describe how the JSON chat log files were structured and how I went about analyzing them, using techniques covered in Chapter 11. I’ll describe the custom app that I wrote to investigate this dataset and explain how I used it to investigate a Discord server called Pony Power, whose members doxed their political enemies. You’ll also learn the inside story of DiscordLeaks, Unicorn Riot’s public searchable archive based on my app, which contains millions of chat messages from far-right Discord servers. Finally, I discuss a major hack of the American neo-Nazi organization Patriot Front that took place four and a half years after the Charlottesville rally. This hack included chat logs from RocketChat, a self-hosted system that Unicorn Riot also hosts in DiscordLeaks.

Like my reporting on the AFLDS dataset, this case study is an example of journalism with real-world impact. My work, along with that of Unicorn Riot, antifascist infiltrators, and other anonymous developers, helped lead to a court settlement against the most notorious American white supremacist leaders and organizations, resulting in over $25 million worth of damages. I hope that this case study will inspire your own work on datasets of structured chat logs, should you obtain them in the future. With the rise of remote work and the increasing popularity of chat platforms like Discord, Slack, and RocketChat, this type of leak is only getting more common.

I’ll start with a brief description of how these chat logs were leaked.

How Antifascists Infiltrated Neo-Nazi Discord Servers¶

Unicorn Riot reporters covered the Unite the Right gathering on the ground in Charlottesville. In the following days, the collective announced that it had received anonymously leaked chat logs from the far-right groups that took part in the rally, and particularly from the Charlottesville 2.0 Discord server. It began publishing articles based on these leaks, showing evidence of premeditated plans for violence, memes about hitting protesters with cars, and posts made after the event celebrating Heather Heyer’s murder. It also published ZIP files containing thousands of screenshots from the infiltrated Discord servers. Researchers, both amateur and professional, immediately began correlating breadcrumbs from these chat logs with photos and videos of the event that were posted to social media to identify specific fascist activists.

Alongside Charlottesville 2.0, other leaked fascist Discord servers had names like Vibrant Diversity, Ethnoserver, Safe Space 3, and 4th Reich. Some servers only had a few dozen users, while others had over a thousand. The most active server at the time, Vibrant Diversity, included a channel called #problematic_oven, where users shared racist memes. The 4th Reich server included a #rare_hitlers channel, where users shared vintage propaganda from Nazi Germany.

Once the reporting of Unicorn Riot and others had made it clear to Discord that Nazis were relying on its service, the chat platform shut down many far-right chat servers and accounts. “Discord’s mission is to bring people together around gaming. We’re about positivity and inclusivity. Not hate. Not violence,” the company said in a statement. “We will continue to take action against white supremacy, nazi ideology, and all forms of hate.” Shutting down individual servers and accounts didn’t work, though; fascists simply created new accounts and set up new chat servers. Just as quickly, antifascists infiltrated those new servers and continued to leak chat logs to Unicorn Riot.

Fascists started spreading conspiracy theories that there were no infiltrators but that Discord itself was selling their chat logs to the Southern Poverty Law Center, a nonprofit that monitors hate groups. “The Charlottesville planning server was leaked, even though it was highly secure and no one could figure out who could have leaked it,” Andrew Anglin, founder of the notorious neo-Nazi website the Daily Stormer, wrote in an April 2018 blog post. “Since then, servers have been repeatedly leaked. People have been doxed without being able to figure out how they were doxed. Repeatedly and consistently, I have been given reason to believe that these are not Discord ‘leaks,’ but data being bought by our enemies.” This wasn’t true, of course. Anglin provided no evidence for the claim, Discord’s privacy policy promises that it doesn’t sell user data, and we know exactly how the data was leaked: antifascists were invited into the group by pretending to be racists.

A few weeks after Unite the Right, I got a hold of some of these chat logs myself and began to analyze them.

Analyzing Leaked Chat Logs¶

In late August of 2017, after Unicorn Riot had started publishing articles based on leaked chats, someone from the collective asked me if I’d like to cover the fascist chat logs for The Intercept. While journalism can be competitive, with each newsroom racing to publish breaking news first without getting scooped, the opposite is often true when it comes to complicated datasets. When it’s clear that there’s no way that a single newsroom has the resources to discover all of the revelations in a dataset, it only makes sense to bring in other newsrooms and share access to the data. This sort of collaboration helps everyone because different newsrooms have different audiences, and it makes real-world impact from the reporting more likely.

My Unicorn Riot contact sent me a ZIP file full of JSON files and screenshots of Discord chats that covered several Discord servers. The JSON files contained more complete logs of everything posted to these chatrooms, while the screenshots captured only specific conversations. While screenshots are initially simpler to use because you don’t need to write any code or use special tools to read them, having the chat logs in a structured data format like JSON is much more useful in the long run. The best way to peruse screenshots of chats is to open individual images, read them one at a time, take note of the filenames that contain interesting content, and refer back to them as needed. This quickly becomes unwieldy when you’re dealing with thousands of screenshots.

I started digging into the JSON files to see what I was dealing with.

Specifically, I used the handy command line tool jq to figure out exactly how this data

was structured in order to find the lists of users and channels and read

the messages in each channel.

NOTE Besides manually reading screenshots and taking notes, another option would have been to index the screenshots in software like Aleph, which you used in Chapter 5. Aleph would then perform OCR on the images, extracting their text and enabling me to search them for keywords. This might be helpful in locating specific messages, but in the end, it’s still not as useful as structured data. If I were dealing with this data today and only had screenshots without access to JSON data, I would definitely rely on Aleph.

Making JSON Files Readable¶

Each JSON file within the ZIP file sent by my source contained the entire archive of chat logs from a given Discord server. For example, one 29MB JSON file was called VibrantDiversityComplete-Sept5at327PM. For the purposes of this book, I’ve renamed it VibrantDiversity.json to make the following examples easier to read.

When I opened this file in a text editor, its contents looked like this:

{"meta":{"users":{"231148326249037824":{"name":"D'Marcus Liebowitz"},"232213403974893569":{"nam

e":"northern_confederate"},"279620004641767424":{"name":"☇Unlimited Power☇"},"23338059623405977

6":{"name":"OrwellHuxley"},"289851780521787392":{"name":"badtanman"},"337421867700715524":{"nam

e":"spadegunner"},"315936522656546818":{"name":"erz1871"},"122932975724789761":{"name":"Archer"

},"201547638129164290":{"name":"SLUG2_"},"288899711929286667":{"name":"million plus"},"25019824

--snip--

This block of data is not very human-readable. As you learned in

Chapter 11, it’s much easier to read JSON

data that’s been reformatted using line breaks, indentation, and syntax

highlighting. Using the jq

command, I formatted it and added syntax highlighting in my terminal

like so:

micah@trapdoor Discord-JSON-Scrapes % cat VibrantDiversity.json | jq

{

"meta": {

"users": {

"231148326249037824": {

"name": "D'Marcus Liebowitz"

},

"232213403974893569": {

"name": "northern_confederate"

},

"279620004641767424": {

"name": "☇Unlimited Power☇"

},

--snip--

Running this command added formatting and syntax highlighting to the file’s contents, but still resulted in 29MB of text madly scrolling through my terminal. To understand the data better, I needed to run more specific commands that would reveal its overall structure.

Exploring Objects, Keys, and Values with jq¶

I could tell by looking at the beginning of the JSON data that the whole

file was one large JSON object, and one of that object’s keys was

meta. I ran the following

jq command to see what other

keys there were:

cat VibrantDiversity.json | jq 'keys'

The output told me that the data for each Discord server includes two

parts, data and

meta:

[

"data",

"meta"

]

Guessing that meta included

the metadata for the server, I ran the following command to determine

the keys of the meta object:

cat VibrantDiversity.json | jq '.meta | keys'

This command piped the output of cat VibrantDiversity.json as input into the

jq '.meta | keys' command.

It looks like there’s a second pipe there, but there’s not. The string

'.meta | keys' is actually

just a single argument into jq. The pipe character is how you chain

multiple jq filters together

so that the output of one gets piped into the output of the next; in

this case, .meta outputs the

value of the meta key and

pipes it into keys, which

outputs the keys from that value.

The output showed me that the metadata included information about channels, servers, and users:

[

"channels",

"servers",

"userindex",

"users"

]

So far, I had only looked at the keys of JSON objects. It was time to

look at some of the content, starting with the servers. By running

jq '.meta .servers', I could

look at the value of the servers key inside the meta object:

cat VibrantDiversity.json | jq '.meta.servers'

The output in Listing 14-1 showed that VibrantDiversity.json lists a single server in the metadata sections, Vibrant Diversity, just as I expected.

[

{

"name": "Vibrant Diversity",

"type": "SERVER"

}

]

Listing 14-1: The list of servers in VibrantDiversity.json

I could tell that this output was an array, since it was a list of items surrounded by brackets ([ and ]).

Next, I wanted to see what channels this server had, so I ran the

following command to view the value of the channels key in the meta object:

cat VibrantDiversity.json | jq '.meta.channels'

Listing 14-2 shows the output of this command.

{

"274024266435919872": {

"server": 0,

"name": "rules"

},

"274262571367006208": {

"server": 0,

"name": "general"

},

"292812979555139589": {

"server": 0,

"name": "effortposting"

},

"288508006990348299": {

"server": 0,

"name": "problematic_oven"

},

"274055625988898816": {

"server": 0,

"name": "music"

},

"343979974241550337": {

"server": 0,

"name": "gun-posting-goes-here"

},

"328841016352440320": {

"server": 0,

"name": "food-posting"

},

"274025126641795074": {

"server": 0,

"name": "share_contact_info"

},

"288901961313550336": {

"server": 0,

"name": "recruiting"

}

}

Listing 14-2: The list of channels in the Vibrant Diversity server

Whereas the output in Listing 14-1 was an

array, the output for .meta.channels was a JSON object, as indicated by the

braces ({and }) surrounding it.

The keys for this object are long numbers, presumably the ID of the

channel, and their values are objects that contain the server and name keys. For example, the channel with

key 288508006990348299 has

the value {"server": 0, "name": "problematic_oven"}. The server value for all of these channels is

0. I guessed that this was

the index of the servers array from Listing 14-1. Since there was only one server in

this JSON file, the index for all of the channels is the first item in

the list, 0. The

name value was

problematic_oven. When I

later read the chats in this channel, it was full of antisemitic posts

and Nazi memes, and the word oven was clearly a reference to the

Holocaust. This was definitely a neo-Nazi chat server.

I wanted to see a list of this server’s users, so I ran the following

command to view the value of the users key in the meta object:

cat VibrantDiversity.json | jq '.meta.users'

Listing 14-3 shows my output.

{

"231148326249037824": {

"name": "D'Marcus Liebowitz"

},

"232213403974893569": {

"name": "northern_confederate"

},

"279620004641767424": {

"name": "☇Unlimited Power☇"

},

--snip--

Listing 14-3: The list of users in the Vibrant Diversity server

Just like the list of channels in Listing 14-2, the output for .meta.users in Listing 14-3 is a JSON object. The keys are long

numbers, presumably the ID of the user, and the values are objects with

just a single key, the user’s name.

So far, I had explored the metadata keys channels, servers, and users, but there was one left: the

userindex key. I ran the

following command to view the userindex key’s value:

cat VibrantDiversity.json | jq '.meta.userindex'

Listing 14-4 shows my output.

[

"231148326249037824",

"232213403974893569",

"279620004641767424",

--snip--

Listing 14-4: The list of user IDs for each user in the Vibrant Diversity server

The output for the .meta.userlist command was a JSON array rather than

an object, and each item in the array was a string that looks like a

Discord ID. Sure enough, the first item, 231148326249037824, turned out to be the ID of the first

user from Listing 14-3, D’Marcus Liebowitz.

At this point I didn’t fully understand the purpose of

userlist, but it soon became

clear, as you’ll see later in this section.

Armed with a basic understanding of the server’s metadata, I ran the

following command to find the keys for the data object:

cat VibrantDiversity.json | jq '.data | keys'

Listing 14-5 shows my output.

[

"274024266435919872",

"274025126641795074",

"274055625988898816",

"274262571367006208",

"288508006990348299",

"288901961313550336",

"292812979555139589",

"328841016352440320",

"343979974241550337"

]

Listing 14-5: The keys to the data object in the Vibrant Diversity server

These keys are the same channel IDs from Listing 14-2, so I guessed that the values of each key contained the actual messages in those chat channels. Because I needed to start somewhere, I decided to view the chat messages from the #problematic_oven channel, so I ran the following command:

cat VibrantDiversity.json | jq '.data."288508006990348299"'

The full argument for this jq command is surrounded by single

quotes. The .data part of

the filter looks in the key data, and the

."288508006990348299" part

of the filter looks in the key 288508006990348299, which is the ID of the

#problematic_oven channel. I put the ID in quotes so that jq would know that this key was a string

and not a number.

As with the first time I used jq to read this JSON file, the output of

this command scrolled through a large block of text, though considerably

less than before. In this case, the output showed chat messages from

only a single channel, rather than showing all of the data in the JSON

file. Listing 14-6 shows just a few chat

messages from the middle of the output.

micah@trapdoor Discord-JSON-Scrapes % cat VibrantDiversity.json | jq '.data

."288508006990348299"'

{

--snip--

"352992491282366485": {

"u": 4,

"t": 1504230368205,

"m": "we need more white girls with nice asses"

},

"352992512752746496": {

"u": 4,

"t": 1504230373324,

"m": "no more gay jew shit"

},

"352992579949690890": {

"u": 1,

"t": 1504230389345,

"m": "you're not allowed to oogle anyone whiter than med"

},

"352992652687441920": {

"u": 1,

"t": 1504230406687,

"m": "if i catch you looking at anglo/celtic/nordic girls you're banned"

},

--snip--

Listing 14-6: Chat messages from the #problematic_oven channel in the Vibrant Diversity server

Just like the channels in Listing 14-2,

this output is a JSON object with keys that contain long numbers. In

this case, these keys appeared to be message IDs, and the values

appeared to be details about that specific chat message. In each

message, the u field

represented the user and the m field contained

the message content. The t

field was a Unix timestamp, the number of seconds or sometimes

milliseconds since January 1, 1970, a common way to represent specific

dates and times in computer science. These particular timestamps were in

milliseconds.

At this point, I knew that I was looking at a conversation between two

neo-Nazis. The top two messages in Listing 14-6 are from a user with the ID of

4, and the bottom two

messages are from a user with the ID of 1. Because the value of t gets bigger with each message, these

appear to be displayed in chronological order. I decided to take a

closer look at the message 352992512752746496, from user 4, with the timestamp

1504230373324.

Converting Timestamps¶

Unix timestamps are a useful way for computers to store an entire date—the year, month, day, and time of day—in a single number. I needed to convert the timestamp associated with that message into human-readable format to find out the date and time when the message was posted.

I used the following lines of code in the Python interpreter to convert

the 1504230373324 timestamp

into a more human-readable Python datetime object:

>>> from datetime import datetime

>>> timestamp = datetime.fromtimestamp(1504230373324 / 1000)

>>> print(timestamp)

The syntax in this code is similar to the code you used to import

modules in Chapter 8. Rather than

import module, this code takes the syntax

from module import resource_name, loading a single

datetime resource from the

datetime module. Next, the

code defines a variable called timestamp and sets its value to the return value

of the datetime.fromtimestamp() function. This function takes the

number of seconds since January 1, 1970, as an argument. Because the

Discord logs are in milliseconds rather than seconds, this code first

divides the Discord timestamp by 1,000 to convert it to seconds before

passing it into the function. The function returns a Python

datetime object.

When I displayed the datetime object with print(timestamp), I could see that this chat message

was posted on August 31, 2017, at 6:46 [PM]:

2017-08-31 18:46:13.324000

I now had an idea of the timeframe in which this chat exchange took place. Next, I wanted to see which users were involved.

Finding Usernames¶

I wanted to find the username for person who’d posted the

352992512752746496 message

in Listing 14-6. The u value for this message was 4, so I checked to see if 4 was a valid user ID from the output in

Listing 14-3 but found that it wasn’t

there; all of the user IDs in that JSON object are 18 digits long. I

turned to the output in Listing 14-4 that shows the value of

userindex in the

meta object. The value of

userindex is an array of

strings, each an 18-digit user ID.

As described in Chapter 11, JSON arrays are

lists of items in a specific order. Objects, on the other hand, don’t

have any order. You select values from arrays using their numerical

indices, starting from index 0 for the first item. Because objects don’t

have numerical indices, there’s no concept of the first, second, or

third item in the object; you could edit a JSON file to rearrange the

object’s items, and it would still be the same object. For this reason,

I guessed that the u value

was actually an index of the userindex array.

To determine which user ID corresponded to the user whose u value was 4, I looked for the value of

userindex at index

4 by running the following

command:

cat VibrantDiversity.json | jq '.meta.userindex[4]'

This command is similar to the one in Listing 14-4, but because it uses

.meta.userindex[4], it

selects the value at index 4

of the .meta.userindex array

and just displays that result. My output showed that this value was the

string 289851780521787392,

an 18-digit user ID:

"289851780521787392"

Now that I had a user ID, I used it in the following command to find the matching username:

cat VibrantDiversity.json | jq '.meta.users."289851780521787392"'

Like the previous command, this command selects just one value to

output. In this case, it selects the meta key, then the users key, then the

289851780521787392 key. The

result is an object that includes a name key:

{

"name": "badtanman"

}

The name badtanman was the username I was looking for.

In the chat logs quoted in Listing 14-6,

the user badtanman is talking to someone with the u value of 1. To find that person’s username, I ran

the same commands, substituting the appropriate ID numbers:

micah@trapdoor Discord-JSON-Scrapes % cat VibrantDiversity.json | jq '.meta.userindex[1]'

"232213403974893569"

micah@trapdoor Discord-JSON-Scrapes % cat VibrantDiversity.json | jq '.meta.users."232213403974

893569"'

{

"name": "northern_confederate"

}

I’d found that the snippet of chat messages in Listing 14-6 was a conversation between badtanman and northern_confederate on the night of August 31, 2017.

Running all of these jq

commands, along with running code in the Python interpreter to convert

timestamps, is tedious. If confronted with a large volume of chat logs,

you don’t want to research every group of messages this way. But when

you’re exploring an unfamiliar dataset for the first time, you need to

manually explore it like this until you better understand how the data

is structured. After doing this preliminary analysis, I could use my new

understanding of the chat logs to write Python scripts or even a full

custom app (like I ended up developing for this dataset) to aid my

research.

Before I actually started writing Python code to more easily parse these chat logs, though, I noticed a file that I’d missed before in the Unicorn Riot ZIP file that might make researching this dataset a lot easier.

The Discord History Tracker¶

The ZIP file from my Unicorn Riot contact had dozens of files in it, most of them JSON files and PNG screenshots, along with a few folders containing other JSON files. I’d immediately zeroed in on the JSON files to analyze their data structure, but until now I hadn’t noticed the file logviewer.html. This was an HTML and JavaScript file that, when opened in a web browser, would allow me to load JSON chat log files and read through them.

After talking with my Unicorn Riot contact, I learned that this local HTML file is part of a piece of open source software called Discord History Tracker. This software, not affiliated with Discord, lets users save an offline copy of everything they have access to in a given Discord server in JSON format. Antifascist activists used this software to exfiltrate chat logs from Vibrant Diversity, Charlottesville 2.0, and other fascist-run Discord servers.

Discord History Tracker included two components. The main component was in charge of actually creating a backup of a Discord server. The user would load the Discord server in their web browser, open their developer tools, and copy and paste the Discord History Tracker JavaScript code into their browser’s console. This would then scrape all of the data in the Discord server and save a backup file in JSON format. The second component of Discord History Tracker was the logviewer.html file, which contained offline HTML software for viewing those backup files.

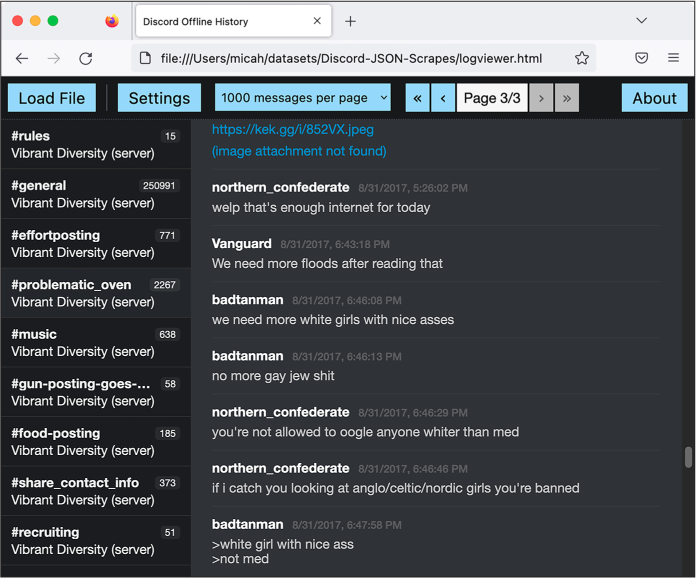

Figure 14-1 shows logviewer.html loaded in a web browser. In the screenshot, I’ve scrolled to the aforementioned messages between badtanman and northern_confederate from the #problematic_oven channel.

NOTE The screenshot in Figure 14-1 shows software from 2017. The Discord History Tracker interface has changed considerably since then. Among other changes, it now saves the data in SQLite databases, rather than as JSON files, and you can view the logs in a desktop app instead of using the logviewer.html file. You can learn more about the software at https://dht.chylex.com.

Figure 14-1: The August 31, 2017, chat between badtanman and northern_confederate,

viewed in the Discord Offline History web app

This offline HTML viewer software made it considerably easier to navigate and read the contents of the JSON files. I could click through the channels on the left, and then read through a page of chats at a time. However, it also lacked some features that would be important for my ongoing investigation:

- There was no simple way to search for individual messages. For example, suppose I wanted to search for mentions of Berkeley, the city I lived in at the time. I would have to click a channel like #general, use my web browser’s search feature to search for Berkeley, and then find which messages appeared in the #general channel. I would also need to change the settings to display all messages per page so I could search them all at once, rather than displaying just 1,000 messages at a time, as shown in Figure 14-1. I would then have to replicate this search for every other channel in the server, and if I wanted to search other Discord servers as well, I’d have to replicate it for each channel in each server.

- The offline viewer only supported looking at one server at a time, but I wanted to be able to search multiple servers at once and also track a single user’s messages across different servers.

- There was no way to generate hyperlinks leading to individual messages. When you’re taking notes for a story based on chat logs like this, it’s helpful to track the messages of interest. Without links, you’ll regularly have to go back and search for specific messages all over again.

I decided to build my own web application to add these missing features. I already had all of the chat logs in a structured format, which is by far the biggest requirement to build a custom app, as you learned in Chapter 10’s discussion of BlueLeaks Explorer. If I’d had only screenshots of the Discord servers, a custom app with these features wouldn’t have been possible. Screenshots aren’t structured data, and there’s no easy way to write software that allows you to browse the chat messages they contain.

A Script to Search the JSON Files¶

As you’ve learned throughout this book, understanding how the data is

structured is a prerequisite to writing code that works with it.

Therefore, I decided to use the knowledge I’d gained from manually

investigating the JSON files with jq to build a simple Python script that

let me search one of the JSON files for keywords. Initially I thought I

might be able to use this script to do all of the analysis I needed, but

that turned out to be wrong; I ended up writing a complete custom app to

investigate this dataset as well. Even so, this first (considerably

simpler) script allowed me to use Python code to express the structure

of the dataset that I’d already gleaned, which simplified the process of

programming the full web app. In this section I go over exactly how my

initial Discord JSON search script worked.

For example, I knew my script needed to be able to display chat messages based on what I searched for. Let’s say I wanted my code to display the following chat message from Listing 14-6:

"352992491282366485": {

"u": 4,

"t": 1504230368205,

"m": "we need more white girls with nice asses"

}

The value of the u key is

4, but now I knew how to

find the actual username of the person who posted this message. First,

my code needed to look in the JSON’s meta object and select the fourth item in

the userindex array, which

is the user ID 289851780521787392. My code then would look again in the

JSON’s meta object, this

time for the users key, and

use that user ID as the key to get this user object:

{

"name": "badtanman"

}

My code would select the name string from that object to get the

username of the message poster, badtanman, and then replicate the whole process

to display the correct username for every message.

I opened my text editor and started writing a Python script, discord-json -search.py, to search one of the JSON files for keywords. Here’s my completed source code (you can also find it at https://github.com/micahflee/hacks-leaks-and-revelations/blob/main/chapter-14/discord-analysis/discord-json-search.py):

#!/usr/bin/python3

import sys

import json

import click

from datetime import datetime

def highlight(message, query): ❶

new_message = ""

index = 0

while True:

new_index = message.lower().find(query.lower(), index)

if new_index > 0:

# Found

new_message += message[index:new_index]

new_message += click.style(

message[new_index : new_index + len(query)], underline=True

)

index = new_index + len(query)

else:

# Not found

new_message += message[index:]

break

return new_message

def display(channel_name, server_name, user_name, timestamp, message, query): ❷

click.echo(

"{} {}".format(

click.style("#{}".format(channel_name), fg="bright_magenta"),

click.style("[server: {}]".format(server_name), fg="bright_black"),

)

)

click.echo(

"{} {}".format(

click.style(user_name, bold=True),

click.style(timestamp.strftime("%c"), fg="bright_black"),

)

)

click.echo(highlight(message, query))

click.echo("")

def search(data, query): ❸

# Loop through each channel

for channel_id in data["data"]: ❹

# Get the channel name and server name

channel_name = data["meta"]["channels"][channel_id]["name"] ❺

server_name = data["meta"]["servers"][

data["meta"]["channels"][channel_id]["server"]

]["name"]

for message_id in data["data"][channel_id]: ❻

# Pull the user data, timestamp, and message body from the message

user_index = data["data"][channel_id][message_id]["u"]

user_id = data["meta"]["userindex"][user_index]

user_name = data["meta"]["users"][user_id]["name"]

timestamp = datetime.fromtimestamp(

data["data"][channel_id][message_id]["t"] / 1000

)

message = data["data"][channel_id][message_id]["m"]

# Is the query in the message?

if query.lower() in message.lower(): ❼

display(channel_name, server_name, user_name, timestamp, message, query)

@click.command()

@click.argument("filename", type=click.Path(exists=True))

@click.argument("query")

def main(filename, query): ❽

# Load the JSON file

try:

with open(filename) as f:

data = json.loads(f.read())

except:

print("Failed to load JSON file")

sys.exit()

# Search

search(data, query)

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

It’s simplest to explain how this script worked from bottom to top,

since that’s how it executed and also how I programmed it. The

main() function

[❽] is a Click command that

takes two arguments: the filename for a JSON file with Discord chat logs

called filename, and a

search term called query.

The code opened the filename that was passed in and parsed it using

json.loads() to turn it into

a JSON object. Then it called the search() function, passing in the data from the

JSON file and the search query.

The search() function

[❸] is where all the magic

happened. I knew from my previous analysis that these Discord JSON

objects had two keys: the data key, which contained the messages in

each channel, and the meta

key, which contained metadata about these messages. My script started by

looping through every channel in data['data'] [❹], then using its channel_id to look up that channel’s name and

server in the metadata [❺]. It

then looped through every message in that channel

[❻] and stored the message’s

username, timestamp, and the message itself in variables.

The code then checked to see if the search query that was passed into

the script as a CLI argument (stored in query) existed in the message (stored in

message) [❼]. As described in Chapter 7, it converted both strings to lowercase

using the lower() method to

make the search case insensitive. If the lowercase version of the

message contained the lowercase version of the search term, the script

then passed all of the relevant variables into the display() function to display the message in the

terminal.

The display() function

[❷] took arguments for

metadata about a message, the message text itself, and the search term

and used those to display the message. This code used

click.echo() instead of

print() to display text to

the terminal, and it used click.style() to apply different colors and

formatting. (You could do all of this just with the print() function, but the click module makes it simpler to style

terminal output.) After displaying two lines of metadata for the

message, the script then displayed the output of the

highlight() function, which

returned the message itself in color with the search term underlined.

The highlight() function

[❶] created an empty string

called new_message and then

made it a copy of message,

the original message it displayed, except with all instances of the

search term underlined using click.style(). It then returned

new_message and displayed it

to the terminal in the display() function.

For example, if I wanted to search VibrantDiversity.json for the term berkeley, I could run:

python3 discord-json-search.py ~/datasets/Discord-JSON-Scrapes/VibrantDiversity.json "berkeley"

The output listed over a hundred chat messages that mentioned Berkeley. Each message showed the name of the channel, the name of the Discord server, the user who posted it and when, and the content of the message. Here’s the first snippet of output, which highlighted the search term in the message with an underline:

#general [server: Vibrant Diversity]

Hector Sun Sep 3 20:19:11 2017

Look at how many antifa were at Boston and Berkeley. We need numbers. We can't have rallies with less than a thousand people now. Even that's a low number.

--snip--

The first message that mentioned Berkeley was a post from the user Hector in the #general channel on September 3, 2017. This user was complaining about the relatively small number of fascists that showed up to their rallies in Boston and Berkeley, compared to the “antifa” counterprotesters.

This script allowed me to search a full Discord server for keywords, but it still lacked several of the features that I wanted: it could work with only one Discord leak at a time, and there was no easy way to browse through and read the data sequentially or to save links to specific interesting messages. I started building out a web application to help me perform these missing tasks.

My Discord Analysis Code¶

I’ve found that after obtaining a large dataset full of structured data, building a custom web application to explore it, as I did with BlueLeaks Explorer, makes it much easier to find its hidden revelations. After writing discord-json -search.py, I spent about a week creating Discord Analysis, a custom web app to analyze leaked Discord chat logs.

Since I wanted to be able to search multiple Discord servers at once, I decided that the best solution would be to convert all of the data from JSON files into a SQL database. I used a Python tech stack that I was already familiar with, Flask (discussed briefly in Chapter 10), for the web app and SQLAlchemy for communicating with the SQL database.

SQLAlchemy is an Object Relational Mapping (ORM) Python module that’s useful for making code that works with SQL databases simpler to write and more secure. ORMs allow you to work with SQL databases in such a way that you don’t have to directly write any SQL code yourself, which means your projects won’t be vulnerable to SQL injection. This web app used Flask-SQLAlchemy, a Flask extension that adds SQLAlchemy support to Flask apps.

While developing my Discord Analysis web app, I was actively using it to research the leaked neo-Nazi chat logs. If I had new questions about the data (like what other messages a user posted) or found that I needed new features (like limiting my search to a single server), I would program them in as I went along. This is typically how I build research tools: I start using them long before they’re complete, and I let the direction of my research guide which features I add next.

In this section, I explain how I went about developing the different components of the app: designing a SQL database, importing chat logs from the Discord JSON files into that database, and building the web interface to research the chat logs. You’ll learn how I used SQLAlchemy to define database tables, insert rows into them, and select rows from them. You’ll also learn how I used Flask to build this web app, including how to make Jinja templates and how to define routes—skills you’ll need if you build your own Flask web apps in the future.

NOTE Fully explaining how to build a Flask and SQLAlchemy web app is outside the scope of this book. Instead, I go over how I went about building this app in broad strokes, which should still be useful if you ever decide to build a similar one yourself. The best way to learn how to make your own Flask app is by exploring Flask’s excellent documentation at https://flask.palletsprojects.com; that’s how I learned. The Flask documentation includes a tutorial that walks you through every step of developing a simple web app. The Python skills you’ve learned from Chapters 7 and 8 are more than enough for you to follow along with the tutorial. You can also find docs for SQLAlchemy at https://www.sqlalchemy.org and for Flask’s SQLAlchemy extension at https://flask-sqlalchemy.palletsprojects.com.

The code for Discord Analysis, which has quietly been public on my GitHub account for years, hasn’t been updated much since 2017, with the exception of some small changes I made when preparing it for this book. I don’t plan on maintaining it. Still, you should be able to get it running locally if you’d like to explore it further, and you can use it as inspiration for your own future projects that use a similar tech stack. Read through this section to see how it works, and then if you’re curious, try getting it running locally yourself.

As I explain the app, I’ll quote sections of the source code. It’s too long to include all of it here, but you can find the full code online in the book’s GitHub repository at https://github.com/micahflee/hacks-leaks-and-revelations/tree/main/chapter-14/discord-analysis. I recommend that you pull up the full source code for each file as I describe how it works.

Designing the SQL Database¶

I started my web app with a Python script called app.py. You can find

the full source code for this file at

https://github.com/micahflee/hacks-leaks-and-revelations/blob/main/chapter-14/discord-analysis/app.py.

First, my code imported the appropriate Flask and SQLAlchemy modules,

created a new Flask app object called app, and created a new Flask-SQLAlchemy

object called db:

from flask import Flask, render_template, request, escape, flash, redirect

from flask_sqlalchemy import SQLAlchemy

app = Flask(__name__)

app.config["SQLALCHEMY_DATABASE_URI"] = "sqlite:///database.sqlite3"

app.config["DEBUG"] = True

db = SQLAlchemy(app)

I started by importing several items from the flask module, like Flask and render_template, that I knew I’d need later in the

program. In the next line, I also imported SQLAlchemy from the flask_sqlalchemy module.

Using the newly imported Flask, I then created a Flask object called

app. Every Flask web app

includes such an object (and usually by that name) to define exactly how

the app will work. I modified the app.config dict to set some configuration

settings, telling it that I wanted to use a SQLite3 database stored in

the file database.sqlite3, and I wanted to turn debug mode on, which

is useful while you’re actively developing a web app. Finally, I created

the SQLAlchemy object called db, passing in app.

For the next bit of code, I’ll introduce you to

a new Python concept that I didn’t explicitly cover in Part III but that you’ve technically been using all

along: classes. In Python, a class is a template for creating new

objects that can store data (using variables called attributes) and

perform actions (using functions called methods). For example, strings

are technically classes. When you run the code s = "example", the variable s is an instance of the string class,

the data it stores is the string example, and it has a bunch of methods you can

call on it, such as s.upper(), which returns an uppercase version of

the string. When you write SQLAlchemy code, you define a class for each

database table. This way, you can write code that works with Python

objects without needing to write the SQL queries yourself.

I started writing code to define the SQL tables that would store Discord

data for servers, users, channels, and messages. For example, the

following code defines the Server class, which represents the SQL table

to store data about servers:

class Server(db.Model):

id = db.Column(db.Integer, autoincrement=True, primary_key=True)

name = db.Column(db.String(128), unique=True, nullable=False)

channels = db.relationship("Channel", back_populates="server")

messages = db.relationship("Message", back_populates="server")

def __init__(self, name):

self.name = name

Using SQLAlchemy requires that you define your own classes. You can

think of this Server class

as a description of a new type of Python object that represents a row in

the server SQL table. Because I defined it as

Server(db .Model), this

class inherited all of the functionality of the db.Model class, which is part of SQLAlchemy.

Inside the class definition, I defined the table’s columns: id (an auto-incrementing number) and

name (a string). Next, I

defined this table’s relationships to other tables, in this case

relating servers to

channels and

messages—both the

Channel table and the

Message table have a

server_id column.

Finally, I defined the __init__() method. When you define a class, you

must call the first argument of every method self to represent this Python object

itself. You can optionally include other arguments, too. The

__init__() method is a type

of method called a constructor, which runs as soon as you create the

object. This constructor sets the value of the object’s name attribute (which you access within the

class as self.name) to the

value of name, which is a

variable passed into the __init__() method as an argument.

For example, to add a row to the Server table in the SQL database for the

Vibrant Diversity Discord server, I could run the code in Listing 14-7. (My Discord Analysis app doesn’t

actually use this code—it loads the servers from the JSON data—but

I’m including this example to help you understand how to use SQLAlchemy

classes to interact with databases without needing to write SQL

queries.)

server = Server("Vibrant Diversity")

db.session.add(server)

db.session.commit()

Listing 14-7: Using SQLAlchemy to insert data into a SQL database

The first line of code creates a Server object by running

Server("Vibrant Diversity").

This would run the constructor method, passing in the string

Vibrant Diversity as

name. The constructor would

then set the value of its name attribute to the name that was passed

in. When the constructor finishes running, the code would save this

newly created Python object in the server variable. The next two lines of code

use the SQLAlchemy object db

to run the INSERT query in

the SQL database and insert this row. The db.session .add() method collects a list of SQL queries,

and the db.session.commit()

method runs those SQL queries on the database. In SQL, sometimes it’s

more efficient to run several queries and then commit them all at once

rather than one at a time.

In other words, the code in Listing 14-7 is

basically the same as running the SQL query

INSERT INTO server SET name='Vibrant Diversity';, except this way all you need to do is

interact with Python objects, not write any SQL yourself. After creating

the server object, I could then access that object’s ID attribute with

server.id or the object’s

name attribute with server.name.

In addition to the Server

table I just described, I also created the following tables, which you

can view in detail in the app.py file at

https://github.com/micahflee/hacks-leaks-and-revelations/blob/main/chapter-14/discord-analysis/app.py:

User A Discord user. I

included the columns id,

discord_id, and

name. The id column is an auto-incrementing number,

and discord_id is the

original ID that Discord itself used. This is useful for identifying the

same user across servers.

Channel A channel in a

Discord server. The columns are id, discord_id, name, and server_id. The server_id column forms a relationship with the

Server table, since each

server has a set of channels. Every Discord server JSON file contains a

list of channels. Adding this relationship means that the SQL database I

was designing would match the data structure in the JSON files.

Message A Discord message.

The columns are id,

discord_id,

timestamp, message, attachments_json, user_id, channel_id, and server_id. The attachments _json column contains extra data from

messages with attachments, like when someone posts an image to Discord.

The user_id,

channel_id, and

server_id columns form

relationships with the User,

Channel, and

Server tables. These also

would match the structure found in the JSON files.

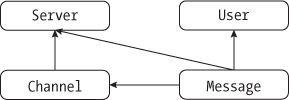

Figure 14-2 shows the relationship between

these four tables. The Channel table includes a server_id column, so it’s related to the

Server table.

The Message table includes columns for

channel_id,

server_id, and

user_id, so it’s related to

the Channel,

Server, and User tables.

Figure 14-2: Relationships between the SQL tables in the Discord Analysis app

My goal for this web app would be to build an interface that allows me to explore the data stored in these SQL tables. I wanted to be able to search all of the messages at once, including from multiple servers, to see which users posted in multiple servers and to be able to generate links to individual messages that I could store in my notes. Before building the web interface, though, I needed to load the database with data from the JSON files.

Importing Chat Logs into the SQL Database¶

I wrote a separate script, admin.py, that I used to import data into

the SQL database. This script took a command as its first argument. If I

passed in create-db, it

would use SQLAlchemy to create the SQL tables that I had defined in

app.py. When I passed in import-json, followed by the filename of a JSON

file, the code would import Discord data from that JSON file into the

SQL database. I also eventually added the user-stats command, which displayed how many

messages each user in the whole database posted, and on which servers.

This admin,py file is too long to include in this chapter in its entirety, but as with app.py, you can find a copy of the complete code in the book’s GitHub repo at https://github.com/micahflee/hacks-leaks-and-revelations/blob/main/chapter-14/discord-analysis/admin.py.

In this section, I’ll explain how I built the import-json command (specifically, the

import_json() function,

which is what gets called when you run import-json), the most interesting part of the

script. This is the code that opens up the JSON files containing Discord

server leaks, loops through all the data, and then inserts it into the

SQL database. As with the discord-json -search.py script, I relied on

my previous manual analysis of the Discord JSON files to write this

code. Basically, this is the part that requires an understanding of the

structure of the original data.

The import_json() function

is too long to display it all here, so instead I’ll display snippets

that explain the general idea of how it works. The function takes the

filename for a JSON file containing Discord leaks as an argument. It

opens this file, loads it into a variable called data, and then uses the information in

data to add servers, users,

channels, and messages to the SQL database. I’ll show the code that adds

users, channels, and messages soon, but first, Listing 14-8 shows the code that adds servers.

print("Adding servers: ", end="", flush=True)

for item in data["meta"]["servers"]:

name = item["name"]

try:

server = Server(name)

db.session.add(server)

db.session.commit()

print("+", end="", flush=True)

except sqlalchemy.exc.IntegrityError:

db.session.rollback()

print(".", end="", flush=True)

print("")

Listing 14-8: Code from admin.py to add servers to the database

This code looped through all of the servers it found in

data["meta"]["servers"],

adding a row to the database for each server that it found. For example,

in Listing 14-1, I used jq to view this list of servers for

VibrantDiversity.json and found that it contained only a single

server. Listing 14-8 uses Python code to

find that same list of servers from the same part of the target leaked

JSON file.

For each server it found, the code stored the server’s name in the

name variable, then tried to

add that server to the database. This code used Python exception

handling, which you learned about in Chapter 7. In the try block, the code created a new

Server object (this

represents a row in the Server table in SQLAlchemy), added that row

to the database using db.session``.add(server), and finally committed the database

changes with db.session.commit(), just like in the SQLAlchemy code in

Listing 14-7. After the server was

successfully inserted into the database, the program displayed a plus

sign (+) and moved on to the

next loop.

When I defined the Server

table in app.py, I specified that the name column should be unique, meaning that

there could be no two rows with the same name column. If SQLAlchemy threw the

sqlalchemy.exc.IntegrityError exception while the script was trying

to add the row to the database, that meant a server with that name

already existed in the database, and the except block should run instead. If this

happened, then the code rolled back the change that it was about to make

and displayed a dot (.)

instead of a plus sign.

Why did I worry about catching these exceptions to begin with instead of just adding rows to the database? As with the programming exercises that you completed in previous chapters, I didn’t write the whole script perfectly the first time and then run it. Instead, I wrote small bits of code at a time and ran them to make sure my script was working so far. This exception handling allowed me to rerun an import on the same JSON file over and over while starting where I left off. If my script showed a plus sign, I knew it had added a new row to the database. If it showed a dot, that meant the row already existed and the script moved on.

You might also notice that the familiar

print() function calls look

odd in Listing 14-8: my code passed in the

end="" and

flush=True keyword

arguments. By default, print() displays the string the user passes in

as an argument, then adds a newline character (\n) to the end. The end argument replaces that newline with

something else (in this case, an empty string). In other words, this is

how I could print a string without moving on to the next line. The

flush=True argument makes

sure that the output gets displayed to the screen immediately; without

it, the output would still get displayed, but not right after the

function call. This allowed me to watch the progress of an import.

After adding servers, the script added users, as shown in Listing 14-9.

print("Adding users: ", end="", flush=True)

for user_discord_id in data["meta"]["users"]:

name = data["meta"]["users"][user_discord_id]["name"]

try:

user = User(user_discord_id, name)

db.session.add(user)

db.session.commit()

print("+", end="", flush=True)

except sqlalchemy.exc.IntegrityError:

db.session.rollback()

print(".", end="", flush=True)

print("")

Listing 14-9: Code from admin.py to add users to the database

This code is very similar to Listing 14-8,

but instead of looping through the list

data["meta"]["servers"], it

looped through the dictionary data["meta"]["users"]. Listing 14-3 shows this JSON object of users from

VibrantDiversity .json. As described in Chapter 8, when you loop through a dictionary, you’re

actually looping through the dictionary’s keys. In this case, the script

stored each key in the user_discord_id variable. Armed with the user’s

Discord ID, it then looked up that user’s name in the metadata.

In the try block, the script

then created a new User

object, this time with both the user’s Discord ID and name, and tried

adding it to the database. When I defined the User table in app.py, I specified that

user_discord_id should be

unique in order to prevent duplicate users. Like Listing 14-8, the code displayed a plus sign when

adding the user to the database and a dot if it hit an error. This

error-handling code would be important when I started importing multiple

servers: if a Discord user was already in the database because they were

a member of a previous server, the code wouldn’t create a duplicate user

for them.

After adding servers and users, the script then added channels, using the code in Listing 14-10.

print("Adding channels: ", end="", flush=True)

for channel_discord_id in data["meta"]["channels"]:

name = data["meta"]["channels"][channel_discord_id]["name"]

server_id = data["meta"]["channels"][channel_discord_id]["server"]

❶ server = Server.query.filter_by(

name=data["meta"]["servers"][server_id]["name"]

).first()

try:

channel = Channel(server, channel_discord_id, name)

db.session.add(channel)

db.session.commit()

print("+", end="", flush=True)

except sqlalchemy.exc.IntegrityError:

db.session.rollback()

print(".", end="", flush=True)

print("")

Listing 14-10: Code from admin.py to add channels to the database

This code is also similar to Listings 14-8 and 14-9. This time however,

it looped through the keys of the data["meta"]["channels"] dictionary, storing each key as

channel_discord_id.

Listing 14-2 showed this JSON object of

channels from VibrantDiversity .json, which you can revisit to remind

yourself what this dictionary looks like. For each channel, the code in

Listing 14-8 stored the name of the channel

in name and that channel’s

server index in server_id.

It then queried the SQL database itself to get the server row in

Listing 14-10 ❶, which should have been added earlier by the

code in Listing 14-9, and stored this value

in server. The SQL query

that the Server.query.filter_by() function call ran was similar to

SELECT * FROM servers WHERE name='``name``';, where name is the server name.

In the try block, the code

then created a new Channel

object, this time telling it the server, the channel’s Discord ID, and

the channel name. As with the previous listings, it tried adding this

channel to the database, displaying a plus sign on success and a dot if

the channel already existed.

Finally, after adding servers, users, and channels, the code added all of the messages, as shown in Listing 14-11.

for channel_discord_id in data["data"]:

# Get the channel

channel = Channel.query.filter_by(discord_id=channel_discord_id).one() ❶

# Loop through each message in this channel

print(f"Adding messages from {channel.server.name}, #{channel.name}: ", end="", flush=True)

for message_discord_id in data["data"][channel_discord_id]:

try:

timestamp = data["data"][channel_discord_id][message_discord_id]["t"]

message = data["data"][channel_discord_id][message_discord_id]["m"]

user_index = data["data"][channel_discord_id][message_discord_id]["u"]

user_discord_id = data["meta"]["userindex"][user_index]

user = User.query.filter_by(discord_id=user_discord_id).first() ❷

if "a" in data["data"][channel_discord_id][message_discord_id]:

attachments_json = json.dumps(

data["data"][channel_discord_id][message_discord_id]["a"]

)

else:

attachments_json = None

message = Message(

channel.server,

message_discord_id,

timestamp,

message,

user,

channel,

attachments_json,

)

db.session.add(message)

db.session.commit()

print("+", end="", flush=True)

except sqlalchemy.exc.IntegrityError:

db.session.rollback()

print(".", end="", flush=True)

print("")

Listing 14-11: Code from admin.py to add messages to the database

This time, this code looped through all of the keys of the

data["data"] dictionary. As

you learned in Listing 14-5, this

dictionary’s keys are the Discord IDs of channels. My code stored each

ID in the variable channel _discord_id. I then used SQLAlchemy to query the

database to load this actual channel row ❶ (the SQL query that this command ran was

similar to SELECT * FROM channel WHERE channel_discord_id=``channel_discord_id, where

channel_discord_id

is the channel ID). After learning what channel it was dealing with, the

code then looped through all of that channel’s messages to add them to

the database, storing each message’s Discord ID as

message_discord_id.

The rest of the code in Listing 14-11 is

also similar to Listings 14-8 through 14-10. In the try block, for each message, the code

stored the timestamp and message in the timestamp and message variables. It then looked up the user

Discord ID from the metadata and queried the SQL database for the

User object

❷, and, if the message

included an attachment, it also created a string called

attachments_json. Finally,

it created a Message object

and inserted this message into the database. As before, the code

displayed a plus sign if it successfully inserted a message or a dot if

that message was already in the database.

Since exception handling ensured admin.py wouldn’t import duplicate rows, I could use this script to import newer versions of JSON files from the same Discord server. For example, if Unicorn Riot’s infiltrator used Discord History Tracker to save another offline copy of everything in Vibrant Diversity a month later, and I imported that new JSON file, it would import only the new messages.

Once this code was written, I used it to import all of the JSON Discord files that I had received from Unicorn Riot. To import data from the Vibrant Diversity channel, I would run this command:

python3 admin.py import-json ~/datasets/Discord-JSON-Scrapes/VibrantDiversity.json

And here is the output:

Adding servers: +

Adding users: +++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

--snip--

Adding channels: +++++++++

Adding messages from Vibrant Diversity, #rules: +++++++++++++++

Adding messages from Vibrant Diversity, #general: +++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

--snip--

Adding messages from Vibrant Diversity, #recruiting: ++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

+++++++++

Import complete

Each plus sign in this output represents a different row of data inserted into the database. The VibrantDiversity.json file added 1 server, 530 users, 9 channels, and a total of 255,349 messages, importing a message at a time.

I then used admin.py to import the rest of the Discord JSON files I had, including chat logs from Anticom, 4th Reich, Ethnoserver, and other leaked servers. For example, next I imported one of the smaller servers called Pony Power, which I’ll discuss further later in this chapter, like so:

python3 admin.py import-json ~/datasets/Discord-JSON-Scrapes/PonyPowerComplete-Sept5at155PM.txt

And here is the output from that command (in this case, I’d already imported the Vibrant Diversity data, and these two Discord channels had some overlapping users, so my script skipped importing some of the users):

Importing: /Users/micah/datasets/Discord-JSON-Scrapes/PonyPowerComplete-Sept5at155PM.txt

Adding servers: +

Adding users: .++++..+++++.+++++..++++.++.+++++++++++..+.+......

Adding channels: ++++

Adding messages from Pony Power, #general-chat: +++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

--snip--

This JSON file included 50 users. The code skipped 17 of them (displaying dots instead of plus signs) because they were already in the database from Vibrant Diversity, and it added 33 new users.

My database was now full of neo-Nazi chat logs, preparing me to build a web interface to explore them. When you’re building a web app to investigate data, you need some data to explore to make sure your app is actually working as intended. If I hadn’t imported the actual data first, I would have had to make up and import some test data so I’d have something to troubleshoot with while building the web app. But I decided to import the real data first because I knew I’d need to write that code eventually anyway.

Building the Web Interface¶

When you build web apps, it’s often useful to split your web pages into

reusable components, like headers, footers, and sidebars. Individual

pages may have their own reusable components, too. For example, the page

that lists chat messages might repeat the same message component for

each message on the page. You define these components in templates,

HTML files that can contain variables and logic, like if statements or for loops. You can render a template

(convert it into HTML) by passing the template file along with variables

into a templating engine, or code that converts a template into HTML.

Flask comes with a popular templating engine called Jinja. To build the web interface to explore the chat logs I’d just imported, I started by creating the layout template in Jinja. In short, I wrote the HTML code that would make up the layout of all of the pages in my web app, but also included Python variables and loops. Listing 14-12 shows the code for layout.html, my layout template.

<!doctype html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Discord Analysis</title>

<link rel=stylesheet type=text/css href="{{url_for('static', filename='style.css')}}"> ❶

</head>

<body>

<div class="wrapper">

<div class="sidebar">

{% for server in servers %} ❷

<div class="server">

<p><strong>{{server.name}}</strong></p>

<ul>

{% for c in server.channels %} ❸

<li{% if channel %}{% if c.id==channel.id %} class="active" {% endif %}{% endif %}><a

href="{{c.permalink()}}">#{{c.name}}</a> <span class="message-count">[{{

"{0:,}".format(c.message_count() | int)}}]</span></li>

{% endfor %}

</ul>

</div>

{% endfor %}

<p><a href="/users">Users</a></p>

</div>

<div class="content">

<div class="search">

<form method="get" action="/search">

<input type="text" name="q" class="q" placeholder="Search query" {% if q %}

value="{{q}}" {% endif %} /> ❹

<select name="s">

<option value="">[all servers]</option>

{% for server in servers %} ❺

<option value="{{server.id}}" {% if server.id==s %} selected="selected" {% endif

%}>

{{server.name}}

</option>

{% endfor %}

</select>

<input type="submit" value="Search" />

</form>

</div>

<div class="messages">

{% for message in get_flashed_messages() %} ❻

<div class=flash>{{message}}</div>

{% endfor %}

</div>

{% block content %}{% endblock %} ❼

</div>

</div>

</body>

</html>

Listing 14-12: The layout.html layout template

The code in Listing 14-12 looks like HTML at a glance, but if you look closely you’ll see that it’s actually a Jinja template. For example, look at the code that adds the CSS (Cascading Style Sheets) file—which defines the page’s style—to the page ❶. The HTML syntax for adding a stylesheet is

<link rel=stylesheet type=text/css href="style.css">

where style.css is

the path or URL of a CSS file. Instead of an actual filename, the code

in Listing 14-12 uses this:

{{url_for('static', filename='style.css')}}

In a Jinja template, putting a Python expression between {{ and }} means Python will evaluate this

expression when the template is rendered. In this case, Listing 14-12 rendered that line as

<link rel=stylesheet type=text/css href="/static/style.css"> because the url_for() function, which is part of Flask, returned the /static/style.css string.

The template in Listing 14-12 also included some for loops. In Jinja, you start a

for loop with the code {% for item in list %} and end it with {% endfor %}. In the left sidebar of the layout,

the template listed all of the Discord servers in the databases

❷, looping through the items

in the servers list one at a

time. (For this template to render properly, I’d need to make sure to

pass servers into the

template as a variable when I render it in the Flask code.) For each

server, after displaying the server name, it looped through all of the

channels in that server ❸,

getting the list of channels from server.channels. For each channel, the code displayed

a link to view messages in that channel followed by the number of

messages it contains.

The template also included a search bar at the top of the page ❹, as well as a drop-down menu with options to search a specific server or to search them all ❺. It also included a list of notification messages ❻ I could use if I wanted to display an error message—for example, if I tried loading a link to view messages in a channel that didn’t exist in the database. Finally, the template displayed the content block for that particular page ❼. While all pages shared this template, the content block differed for each page.

After starting on my templates, I wrote code for a handful of routes,

which let the web app know which page the user’s web browser was trying

to view. In web development, you can think of a route as a path for a

web page, except it can include placeholders. For example, if the web

app is hosted at http://localhost:5000,

and the Python code defines the route /search for the search page, users can view

that route with the URL

http://localhost:5000/search.

The home page route (/),

shown in Listing 14-13, was by far the

simplest one in my web app. This page displayed the message “This is a

web app that will let you research the alt-right chatroom leak,

published by Unicorn Riot.”

@app.route("/")

def index():

servers = Server.query.all()

return render_template("index.html", servers=servers)

Listing 14-13: The home page route (/)

In Flask, each route is a function that returns the HTML for that web

page. The index() function

starts with the @app.route("/") decorator, which is how Flask knows

that the / route should call

this function. This function first runs a SQL query to get all of the

servers in the database, stored in the variable servers. It then calls the

render_template() function,

rendering the index.html template, passing the servers variable into the template, and

returning the HTML it receives.

Listing 14-14 shows the code for the index.html Jinja template that was rendered.

{% extends "layout.html" %}

{% block content %}

<h2>Alt-right chatroom research</h2>

<p>This is a web app that will let you research the alt-right chatroom leak,

published by Unicorn Riot.</p>

<p>Click on channel names to browse them. Search for keywords. Viewing

individual messages will show you the whole conversation from an hour

before and after that message.</p>

{% endblock %}

Listing 14-14: The index.html template

The first line of code in this template means that Jinja should render

the layout.html template but replace

{% block content %}{% endblock %} with the content block defined

here—some text that says, “Alt-right chatroom research” and a brief

description of the web app. Also notice that in Listing 14-13, I passed the servers variable into the template; the

layout.html template in Listing 14-11

used this variable to make the list of servers in the sidebar.

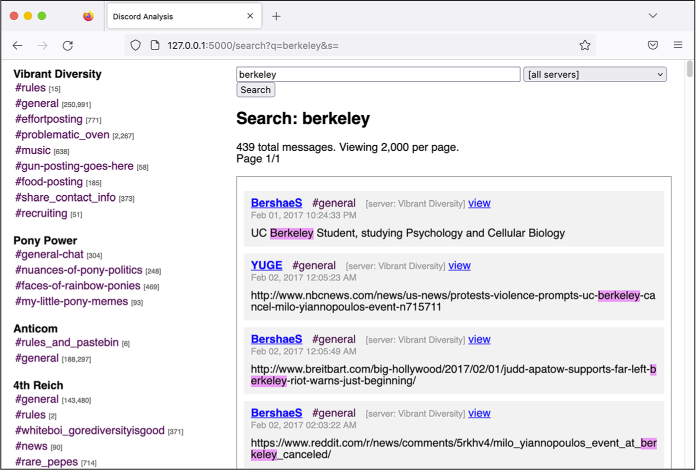

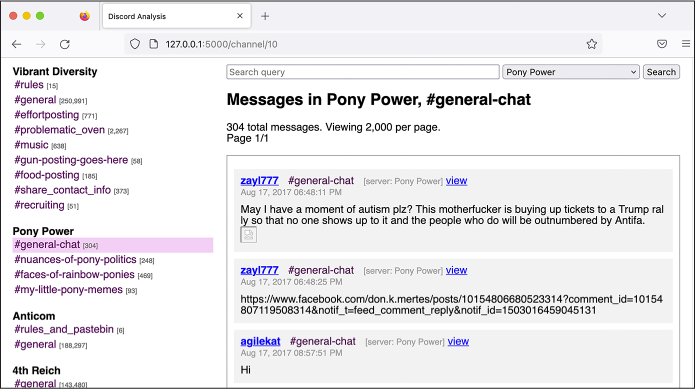

Figure 14-3 shows what the app’s home page looked like at this point, with the home page text as defined in index.html and with the servers on the left and the search bar at the top as defined in layout.html.

Figure 14-3: The home page of my Discord Analysis web app

Let’s look at one more route that does a bit more than the / route, the /search route, which will help explain how one

of the web app’s core features—searching the chat logs—works. Here’s

the Python code:

@app.route("/search")

def search():

q = request.args.get("q")

s = request.args.get("s", 0)

if s == "":

s = 0

page, per_page = get_pagination_args()

server = Server.query.filter_by(id=s).first()

messages = Message.query

if server:

messages = messages.filter_by(server=server)

pagination = (

messages.filter(Message.message.like(f"%{q}%"))

.order_by(Message.timestamp)

.paginate(page=page, per_page=per_page)

)

if server:

description = f"Search {server.name}: {q}"

else:

description = f"Search: {q}"

servers = Server.query.all()

pagination_link = f"/search?q={q}&s={s}"

return render_template(

"results.html",

q=q,

s=int(s),

servers=servers,

pagination=pagination,

pagination_link=pagination_link,

description=description,

)

The search() function starts

with the decorator @app.route("/search"), so Flask knows that the

/search route should call

this function. At the beginning of the function, I defined the

q, s, page, and per_page variables as the values from the URL’s

query string. For example, if the URL ends in

/search?q[=]berkeley, then this code would set the

value of q to the

berkeley.

I got this query string information from the Flask variable

request.args, which is a

dictionary containing all of the values after the ? in the URL. The code got the value of

the q key in this dictionary

by evaluating request.args.get("q"), but request.args["q"] would work just the same. When using

the .get() method on

dictionaries, you can choose default values, as I did in the following

line. The expression request.args.get("s", 0) looks through request.args for the key s and returns it if it finds it. If the

expression doesn’t find s,

it returns 0.

On the search page, q is the

search query and s is the ID

of the server to search (if s is 0, this means I want to search all

servers). The page and

per_page variables are used

for pagination, which determines how an app displays a limited number

of results per page. The page variable is the page number, and

per_page is the number of

results per page.

Since three of the routes in my app used pagination (/search, /channel, and /user), I wrote the code to find the

page and per_page query strings in the function

get_pagination_args(), which

allowed me to just call that function instead of repeating the same code

in multiple places.

I then queried the SQL database for the server

with the ID stored in s,

saving the result as server.

The server variable is used

to optionally search a single Discord server, rather than all of them.

If the SQL database doesn’t have any servers with that ID, then

server is set to

None, which means the app

should search all servers. I then started building the SQL query to

search for all of the messages, storing the results in the variable

messages. If this search was

limited to a specific server (that is, if there’s a value for

s), the code modified

messages to filter just by

messages from that server. Finally, I used the SQLAlchemy pagination

feature to run the SQL query, making sure to select the correct page of

results, storing the search results in the variable pagination. Part of the SQLAlchemy query included

Message.message.like(f"%{q}%") to ultimately run a SQL query that

used SQL’s LIKE operator,

which did a case-insensitive search for any messages containing the

string q, as described in

Chapter 12.

In the following if

statement, my code defined the description variable as a description of the

search, showing either just the search query or both it and the name of

the server being searched. It then loaded all of the servers with

servers=Server.query.all(), which the layout.html layout